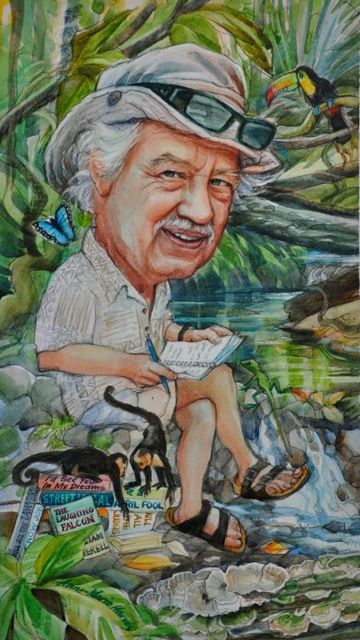

The Advocate is the mouthpiece (so to speak) of the Vancouver Bar Association, and not long ago it ran this tell-all profile of Bill Deverell by his former law partner, Jay Clarke, a prolific crime writer known more widely by his nom de guerre, Michael Slade. The illustration is by Anne-Marie Harvey, a talented Vancouver arist and tongue-in-cheek portraitist, drawn from a scene captured by her in the jungles of Costa Rica.Clarke a.k.a. Slade was careful to preface the piece with this disclaimer: Warning: This memoir contains scenes of sex, humour, and violence. Reader discretion is advised.

Here it is:

Sometimes you’re in the right place at the right time. The right place was Bill Deverell’s law firm and the right time was 1971, the year I began articles under Bill during one of the most exciting eras of the criminal law in Vancouver — when the courtrooms were inhabited by characters so zany they seemed drawn from fiction (and who, conversely, inspired much of Bill’s fiction). I don’t mean just the characters sitting in the dock. I mean the lawyers. And the judges. I call those the Golden Years.

One of those inimitable characters was Bill Deverell himself. As his student and acolyte, I fell under his multi-faceted influence: a journalist, a founder of the B.C. Civil Liberties Association, an unelected politician, a hotshot criminal lawyer (he both freed them and put them away), a multi-award-winning novelist, a fire-in-his-belly environmentalist, about the best principal an articling student ever had, and a bust-your-gut funny guy.

Let’s look at those chapters of his life seriatim.

Journalist. Regina-born and the son of an underpaid socialist newspaperman (more on that below), Bill worked his way through law school as a reporter, night edition editor, full-time staffer at the Canadian Press and several dailies, and still had time to be editor of his university student newspaper.

In 1962, he was a year from taking his law degree at the University of Saskatchewan when the Vancouver Sun headhunted him from the flat, dry prairies to cover, inexplicably, the waterfront beat. (His first byline began: “There’s a parking problem in Vancouver’s harbour…”)

In those glory days of the print media, the Sun’s editorial room was a bedlam of shouts and ringing phones and clanging typewriter carriages at deadline, a pressure-cooker atmosphere that I suspect accounts for Bill’s legal arguments being so tightly reasoned, the driving prose in his novels so readable.

His fellow newshounds and columnists are now local legends: Jack Webster, Jack Scott, Barry Mather, Al Fotheringham, Denny Boyd, Simma Holt, cartoonist Len Norris. As I recall from my own term there as a copy runner, the crime reporter would bring a bottle of Scotch to work each day and take the empty home at night.

Bill returned to Saskatoon the next year, winning the McKenzie Prize in Evidence, graduating third in his class, and leading the campus New Democrats to a mock parliamentary victory (and selling his long-time friend and soon-to-be-premier, Roy Romanow, his first NDP membership — on a promise he’d be made his external affairs minister).

Civil Rights Activist. In a piece Bill wrote years ago in this very journal, he tells the story of how his articles began:

“In 1963, I sought refuge from the biting Prairie winters to seek articles on the West Coast, though as a late-arriving stranger to those shores, I got last pick: a struggling suburban practitioner who, on learning I could type, immediately laid off his secretary. As a civil libertarian, I had hoped to earn my spurs in the criminal courts, fighting for grand causes, but during half a year of typing my own letters I managed to squeeze in only one trial: a juvenile court matter involving a stolen Popsicle.” Which he lost, after tying up the court for an entire day on a complex jurisdictional issue.

He switched his articles to Gordon Dowding, the feisty MLA and later House Speaker, who invited him to join the Board of the nascent Civil Liberties Association. For a year he served as its executive director, running an office from his North Vancouver basement suite and fielding calls from the wronged, the oppressed, and the obligatory cranks. He earned a name doing this, and, he ruefully admits, an extensive non-paying clientele.

Politician. Surely the least notable of Bill’s ventures, as he himself admitted in his Author’s Note to his political novel, Snow Job: “At the risk of shaking readers’ confidence in my sanity, let me make confession: I was once an ambitious (though inept) politician. As a young lawyer running for the New Democrats, I’d made two disastrous tries for Parliament and one for the BC legislature, in Vancouver Centre, ultimately proving myself so hapless at hustling votes that I was punished by losing a nomination — by a single vote — for the succeeding election. Without me to drag down the ticket, the NDP went on to win handily and formed a government.”

The candidate who won that nomination, Gary Lauk, went on to be Attorney-General, an office that Bill would assuredly have snagged were it not for one missing X. But the consolation prize for a wannabe novelist was this: “In sublime irony, that one-vote loss freed me to pursue a different dream, long held. Had I achieved office, I might never have written anything more entertaining than a sitting member’s cynical memoir of frustration, compromise, and lost ideals.”

Trial lawyer. Desolated by the failure of his political ambitions, Bill plunged ever more single-mindedly into his practice: mostly criminal and civil rights, but with a fair dollop of tort actions and labour law.

Was there ever a more rousing time to practise criminal law than the 1960s and ’70s? I doubt it. Sex, drugs, and rock-’n’-roll, yes, but it was also the era of great civil liberties breakthroughs, gender equality, racial equality, marches, demonstrations, confrontations with those who controlled the levers of the law and weren’t afraid to abuse their power.

You couldn’t pick up a paper without reading about the legal exploits of Bill Deverell. (Mind you, he knew all the reporters, and they all knew him.) But he got the headline cases, and his years of volunteer service for the BCCLA had made him a magnet for civil liberties issues.

Back in his early years, Legal Aid was paying $35 a head for defences of the indigent, and Bill would stockpile as many as he could, sometimes ten a day: pot possessors, arrest resisters, disturbance causers, Vag A’s, Vag B’s, Vag C’s. (In the bad old days, one could be convicted for being found in a public place while unable to give a good account of oneself, for begging, or being a common prostitute: Vagrancy A, B, and C respectively.)

Deverell, Harrop, Wood, and Powell was definitely the go-to law firm when I graduated from UBC: three barristers plus a solicitor to tidy up their messy accounts. The late, great Dave Gibbons also enjoyed a spell with the firm, as did Madam Justice Nancy Morrison. Judge Josiah Wood, who has served three levels of BC’s judiciary (in no particular order) was Bill’s first articling student.

With a desperate craving to secure articles where the action was, I mailed my c.v. to the firm. A callback asked if I would meet the partners at 10:30 Saturday morning to find them all looking somewhat hungover. (So much so that they couldn’t find the energy to read that c.v.)

Here, slightly fictionalized in Bill’s comic masterpiece, Kill All the Lawyers — all names are changed, including mine — is how Bill recalls it:

Wentworth had been near the top of his graduating class and was entertained by scouts from several large firms. But he was idealistic and wanted to fight for people’s rights. For law graduates set upon this course, there was only one firm in Vancouver, that holy shrine of the underdog, the office of Pomeroy, Macarthur, Brovak and Sage.

So Wentworth Chance applied for articles — as did thirty-seven other classmates — and ultimately found himself in the library-boardroom looking upon his gods. They seemed out of sorts, as if hung over, especially John Brovak.

The interview went something like this:

Brovak: “How many more eager beavers are out there?”

Sage: “I counted five anyway.”

Brovak: “Aw, God help me. I need to go home and conk off.”

Macarthur: “Yeah, I have brain-fade. Let’s just take this guy and get it over with.”

Brovak: “You got a car?”

Chance: “I can’t afford a car.”

Macarthur: “Well, you better buy a bicycle because you’re going to be pedalling a lot of paper around.”

Native rights counsel Louise Mandell, also Bill’s student, tells an equally entertaining (non-fictional) story of how Bill hired her. It was his disconcerting custom to ask interviewees to list any faults they might have. Without hesitation, she replied: “I’m short, Jewish, and a woman.” Bill burst out laughing and said: “You’re hired.”

Soon after my own interview, Bill called me into his office at day’s end. I fully expected to be told he’d erred and wished to rescind the offer. So I slunk in to find Bill alone in the office, sitting with his feet up on his desk, reading a factum and sipping a beer.

Legal Aid had turned down a jailhouse lawyer named Chudzik for an appeal. Not to be thwarted, he’d filed his own fifty-page brief on the intricacies of certiorari, prohibition, and mandamus. The Appeal Court took one look at that mess, spied Bill waiting for his case to be called, and strong-armed him into serving as amicus curiae.

Bill passed me a beer and Chudzik’s factum. “This seems like gibberish,” I ventured.

“You’ll encounter similar in some of the judgments from the provincial bench. I’m the judge. Argue it.”

So well developed was Bill’s sense of advocacy (as well as humour) that after a few more beers we’d deciphered Chudzik’s ramblings, and not only did we have tears in our eyes from laughter, but Bill had given me a memorable lesson in the art of advocacy.

Among the firm’s few corporate clients was a purveyor of adult literature and marital aids who came by to seek an opinion as to whether he risked arrest by selling his latest prototype: a dildo sheathed in a flesh-coloured plastic phallus. When he flicked the switch on the vibrator’s tail, it jumped out of his hand and whirled around on the floor, causing an eyebrow-raised secretary to react wryly: “This is better than playing spin the bottle.”

Ultimately, Bill told me to get rid of the thing, declaring: “We’re running a reputable firm.” I dropped it in my briefcase, and forgot about it until later that night when we got cornered in a restaurant during the infamous Gastown riot. As Maple Tree Square exploded in a pandemonium of fleeing stoned protestors and baton-wielding mounted policemen in riot gear, I remembered the dildo and pulled it out of my bag.

“Bill, what if the cops find this?”

“Then I suspect you’ll get charged with carrying a very offensive weapon.”

Freedom of expression cases had become an office specialty, and few lawyers have done more to blunt the obscenity laws than Bill, with landmark rulings at trial and appeals that frequently took him to Ottawa. In one key appeal, convictions against the cast of a play, The Beard, were erased. He regularly defended The Georgia Straight as well as a plethora of book and magazine sellers in what he fondly remembers as the Dirty Assize. That involved thirty-odd Mom and Pop stores accused of selling hundreds of plastic-wrapped books of dubious literary merit: Hump Happy and such. The Crown made the error of proceeding by indictment; then, faced with the prospect of the courts being clogged by three dozen trials of more than a month each, caved.

But the case Bill most enjoys recounting was the defence of a Fourth Avenue head shop for selling a Kama Sutra calendar — it depicted stick figures copulating, and as Bill tells it, the magistrate convicted January through March, acquitted the remaining spring and summer months, and fined November and December a hundred dollars each.

I could write an entire book on Bill’s murder cases — but he’s doing a pretty good job of it himself: many have provided grist for his novels. Including the one I’m about to recount, a prosecution he did on retainer to the Attorney-General. Bill tells me it’s the inspiration for his work-in-progress:

John Wurtz and Daniel Eyre were driving west from Toronto to check out Vancouver while sharing a novel titled The First Deadly Sin, and speculating about whether the murder of a stranger might, as in the novel, produce an erotic thrill. Wurtz took the fantasy seriously, and in Vancouver picked up a loner and stabbed him to death (57 times with a pair of scissors) in his basement suite.

Wurtz underwent a lacerating cross-examination, became tied up in his lies, and after conviction, while being led off to serve a life sentence, he passed by counsel table and whispered to Bill: “One day, I’m going to get you.” A few years later, the police warned Bill that Wurtz had escaped from Kingston Pen. He hasn’t surfaced since, though his parents subsequently received by mail a mysterious urn with ashes from an unknown source. Bill, whose writing studio is a cabin in the woods, says he will often jump on hearing the sound of a twig breaking or the wind whistling through the cedars.

It seems ironic that the only murder case Bill ever lost is the subject of his one non-fiction book: A Life on Trial, an amazing fact situation involving a gay man named Frisbee, the employee (butler, secretary, chauffeur, hairdesser, cook, and dancing companion) of a wealthy widow alleged to have been beaten to death with a booze bottle in a luxury suite of an Alaska cruise ship. The motive: a prospective change in her will that would disinherit him from her millions. (He’d also had an affair with her late husband, a wills and estates lawyer. Frisbee’s partner was a self-professed psychic and a minister with a mail-ordered degree.) Enough said. A Life on Trial is also chock-full of anecdotes about Bill’s court career.

Novelist. In 1977, Bill took a year-long sabbatical from his practice, hoping to find his literary muse on the ten bucolic acres of farm and woodland on Pender Island. He immediately went into an acute state of writer’s block, an affliction prompted by his literary father’s scorn of so-called popular fiction.

He describes his dad thus in a newly published collection of Margaret Laurence Lectures titled A Writer’s Life: “A journalist, a voracious reader of classics who quoted Shakespeare on occasions appropriate or not, recited Keats and Shelley when in his cups — which regrettably was not an uncommon condition — and regularly insisted I would be better off reading Moby Dick than the Lone Ranger. Secretly, he wrote — stories that he mailed off to the New Yorker but that never saw the light of print. He showed me such a piece once, and with all the cool superiority of the teenage snob I was, I praised it insufficiently, and I don’t think he wrote after that, and I have ever since carried the burden of my impertinence.”

Bob Deverell died of cancer while Bill was on that sabbatical.

“As of that time, I was still suffering under the grinding weight of my writer’s block, despite several blind forays into a self-conscious Can-Lit style that I assumed was demanded by the industry. But suddenly I underwent a catharsis. It was this: I had been afraid to write because of my father, afraid to follow in the footsteps of his failures, but also cowed by something larger, the sense that I would disappoint him if I did not follow the true and noble path—produce a work that would attract that adjective he most admired: ‘literary.’

“Despite my sadness at his death, now I was unchained, I was free to junk earlier efforts. I had been a criminal lawyer, I had defended the innocent and the guilty and prosecuted the vilest murderers. I knew something of the underbelly of my city, Vancouver, I knew something of the pompous theatre of the courtroom. I was nearing forty, I was determined to break into print with both guns blazing. I would write a thriller.”

He added: “I found inspiration from Hilaire Beloc:”

When I am dead, I hope it may be said:

His sins were scarlet, but his books were read.

Suddenly it was as if a dam had been breached, and Bill found himself muttering to his typewriter, “My God, Remington, I think I can write.”

And what he began writing was a novel about a prosecutor who secretly chips heroin and runs afoul of a vengeful importer of heroin with a penchant for inflicting tortures with acupuncture needles.

Needles came out to wide acclaim in 1979. It won both a $50,000 prize and a Book of the Year award

Not everyone got it. Larry Still, court reporter for the Sun, began his review by quoting the obscenity definition from the Code (“sex, horror, cruelty, and violence”), and announced that none of the characters had any redeeming features except the judge: the lawyer-author had cautiously avoided sticking it to the judiciary. (He may have taken affront because Bill’s publisher, as a publicity gimmick, had mailed hypodermic syringes to all the book editors. Bill was quoted in the Sun as explaining it was just hype.)

Needles’s dedication reads: “To the memory of my father, who died recently. He was a good journalist, and he despised pretension.” Could it be that sometimes blessings come in heartbreaking disguise?

Bill’s second thriller, High Crimes, sprang directly from one of his cases, an entrapment setup in which the RCMP and DEA supplied unwary Newfie smugglers with the ship, captain, crew, and the dope (seventeen tons of low-grade pot). A Sat-Track device hidden aboard stalked them to an inlet north of Tofino, where contact was lost in dense fog during the transfer to a pair of fishing vessels — despite the presence of a hundred officers on the surrounding hills and in boats.

Legend is the Newfies got away with enough tonnage to pay Bill’s fees. While researching the novel, ten years later, in Colombia, he stopped off in Costa Rica, fell in love with that beguiling little democracy, and soon afterwards purchased four acres in the once sleepy village of Manuel Antonio, now a chic tourist destination. (And that’s where he is, as I write this.)

Others of his cases, clients, and his courtroom friends and foes, continued to fuel the muse. In The Dance of Shiva, a civil rights lawyer falls under the hypnotic sway of a guru charged with a mass killing. Bill had acted for a guru with apparent hypnotic powers and, allegedly, a bent for fraud.

Trial of Passion, which won the Dashiell Hammett Award for literary excellence in crime writing in North America, was kindled by an infamous case in upscale Shaughnessy involving booze, bondage, and allegations of rape.

Though typecast by his publisher, his reviewers, and bookstores, real and online, as a writer of “murder mysteries,” he has become reluctant to shed blood (unlike the author of this piece). Indeed, in several of his recent novels he hasn’t been able to produce a body. Genre-wise, is it fair to say Bill’s noir has turned to cozy?

In Slander, a young Seattle civil rights attorney gets sued for outing a powerful judge as a serial rapist. (It was Bill’s first venture in creating a woman protagonist, and he elicited comments on the manuscript from feminist friends. Margaret Atwood reassured him: “Well, you haven’t stuck a tampon in anyone’s ear.”)

His novels have not all been courtroom dramas. The Laughing Falcon, set in Costa Rica, is a double sendup of the thriller and the romance genre. Mind Games creates a neurotic forensic shrink who is pathologically absent-minded, and phobic about heights, enclosed spaces, and pretty well everything else. Nor has Bill stuck to print. He created Street Legal for the CBC.

Bill’s hugely popular Arthur Beauchamp series (Trial of Passion plus his last six) sets his self-doubting, curmudgeonly protagonist – recovered alcoholic, recovered cuckold, organic farmer, courtroom dazzler – like a pigeon among the playful cats of not-so-fictional Garibaldi Island, whose wily rogues constantly outwit the eminent barrister. Kill All the Judges and Snow Job were both finalists for the Stephen Leacock Prize for Humour.

Twice he has won the Ellis prize for best Canadian crime novel. Last May, the Crime Writers of Canada bestowed upon him a Lifetime Achievement Award, adding to his prior international credits.

In 2011, Simon Fraser University “hooded” Bill as a Doctor of Letters, honoris causa. He was lauded for defending “the ideals and individuals animating this messy beast we call a free society.” Both as first-class counsel and as a writer “of the highest calibre,” Dr. Deverell “laboured tirelessly to protect freedom of expression.”

Environmentalist. In life and in fiction, Bill, who calls himself an eco-neurotic, has become Green with a capital G. He has dedicated novels (twice) to EcoJustice Canada, and to the defenders of the Clayoquot, and has given time and his name to West Coast Environmental Law causes. Almost all his later novels bear sub-plots replete with eco-issues and campaigns. In Kill All the Judges, Beauchamp’s wife, Margaret Blake, wins election to Parliament as Canada’s first Green MP.

Indeed, fellow lawyer Elizabeth May credits him (with her tongue only slightly in her cheek) with getting her elected. She wrote:

“There has never been a truer case of life following art, as me becoming the first Green MP. Not only did Bill make it happen in fiction, he played a key role in making it happen in fact. He urged me to run in Saanich Gulf Islands, and he and Tekla offered constant support…What Bill doesn’t know is that I have organized my Parliament Hill office on the mental image he painted (in Snow Job) of Margaret Blake’s office of busy staffers and pell-mell activity. I have only one favour to ask of my friend/mentor/magician. Can you please hurry along with the Arthur Beauchamp sequel in which he and Margaret set up organic farming at 24 Sussex Drive?”

In conclusion: Bill has an aura about him. He inspires confidence. Not only did he make a lawyer out of me, but he generously gave me the motivation and encouragement to try writing, too. Plus – unbeknown to Bill - the inspiration. How shall I put it? Who could have guessed the literary value of that “offensive weapon” discarded from Bill’s office in 1971? Plot-wise, it launched a career that has kept me writing thrillers for thirty years.

I sometimes wonder if Bill feels like Victor Frankenstein, on confronting his Monster? (Pictured below: Michael Slade, a.k.a. Jay Clarke)

If you’re old enough to have walked the halls of our lost Old Bailey (which the penny-pinchers should damn well return to us for criminal trials), or young enough to wish to time-travel back to our profession’s Golden Age, sit back with Bill’s latest: I’ll See You in My Dreams, a then-and-now saga populated with real-life titans from the 1960s: Angelo Branca, Hugh McGivern, Harry Rankin, Larry Hill, and Bert Oliver, while reveling in the antics of Bill’s Merry Pranksters.

You’ll soon grok (a ’60s term) why, when the Canadian Bar Association went searching for a poster boy to epitomize what could be accomplished with a law degree, they produced the poster lower right:

UPDATE:

Since I'll See You in My Dreams, published in 2011, Deverell has authored three more courtroom thrillers.

Sing a Worried Song was inspired by a murder case that he prosecuted. The story flashes back to 1987 when, after a gruelling trial with perilous setbacks, the accused makes a death threat to the prosecutor (alias Bill Deverell). Flash forward to present time, and that threat becomes very real.

Whipped has Beauchamp defending his politician wife, Margaret Blake, against a $50 million slander suit issued by an arrogant cabinet minister with a penchant for being ridden bareback by a whip-yielding dominatrix. Meanwhile a reporter who keeps a devastating secret is running from the Mafia, and New Age Grope-Group has captivated Arthur's island.

Stung is an environmental thriller which Beverley McLachlin, former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, described as: “Irreverent, bawdy, and boisterous, Deverell’s foray into radical environmentalism on trial keeps the reader riveted until the last page. The courtroom scenes are brilliant.”

The Long-Shot Trial takes Arthur back to the 1960s,his first major trial. The NY Times Review: Far be it from me to say whether William Deverell’s THE LONG-SHOT TRIAL (ECW Press, 250 pp., paperback, $21.95), the ninth novel to star the quick-witted defense lawyer Arthur Beauchamp, will be his last; that said, Deverell is 87, and the book is shot through with lament and mourning. Beauchamp, about the same age as the author, has been provoked into writing his memoirs, concentrating specifically on a 1966 case in which a young woman alleged that her employer had raped her and then shot him dead.Beauchamp gets tasked with the case at the last minute, and he’s certain it’s not winnable. But all he needs is reasonable doubt to clear his client. As he reminisces, the present day occasionally intrudes — minor conflicts with his wife; interactions with his would-be literary agent. Deverell paces his story beautifully and weaves in somefinal surprises

In 2015, Bill received his second Doctor of Letters, from his alma mater, the University of Saskatchewan. The USask president, Dr. Peter Stoicheff, wrote: “Mr. Deverell is widely regarded in literary circles as a national treasure and we hold great admiration for all he has accomplished as an award-winning author, lawyer, environmental activist, and as a champion of civil rights. We are pleased to have this opportunity to celebrate his many achievements since graduating from the University of Saskatchewan and we are extremely proud to call him one of our own.”

Margaret Laurence lecture – William Deverell, May 31, 2001

I had a brief and pleasant correspondence recently with Carol Shields, in which I informed her I was both awed and honoured to be stepping into her very large shoes – metaphorically speaking - and I recounted to her a recent speech anxiety dream. I was here, on this stage, and when I looked at my notes they were blank; I was in fear that I was going to have to invent words, to make something up.

I suppose the symbolism stems from the dread of the blank page from which we all occasionally suffer. Either that, or the fear of naked exposure suggested by the topic of “A Writer’s Life”—though perhaps my anxiety was provoked by my history of wrong-footing myself at these conventions of writers. Despite whatever respect I may have gained before a larger audience, I am considered by my own community of creators as a source of amusement if not pity.

My résumé of calamities at AGMs of the Writers’ Union include the following.

One chipped tooth suffered when I played the gallant fool, trying to change a flat tire on Marilyn Bowering’s rent-a-car.

A week of temporary near-blindness—this was in the years of my vanity, when I wore contact lenses—the result of have soaked them in the cleaning solution before wearing them through dinner.

And one time I lost my return air ticket, somewhere in the bowels of the Queen’s University campus.

So do not be surprised if I step off the edge of this stage tonight into the lap of Penny Dickens.

Given the title of this series, I thought I should speak of some of the unvarnished edges of a writer’s life—particularly so because I have a captive audience of fellow writers. Margaret Laurence once referred to her fellow members of this odd profession as a tribe, and it takes some bravery to quarrel with her, but art —and Margaret Laurence knew that well—is a task for loners, and it is only at occasional celebrations such as this that we writers come together. (Unless one has the misfortune to live in Toronto.)

Yet she is right in that there is a sharing in spirit, a sharing in the satisfaction of giving voice to the muse within. There is also a sharing in the pain of freeing that voice, and what I propose to talk about are some of the more stressful aspects of that collective experience. Those of you who are members of the Writers’ Union will relate to much of what I will say. As to those here who are yet unpublished, I can only hope that by the end of my talk I will have discouraged all but the most reckless and obsessive from taking up this career.

My first inkling that a writer’s life was not a constant gala came when I was flown to Toronto to be presented with the Seal Prize. Though McClelland and Stewart did not consider me worthy of a first-class ticket, alcoholic drinks in those days were free in the steerage compartment, and I was in a celebratory mood.

On arrival in the city I was spirited into a hotel salon by a horde of publicists whose task was to groom me for a press conference the next day. I needed grooming. Determined not to look like a stuffy lawyer, I was in jeans, and had grown my hair below the shoulder. Everyone else was in suits, the men with ties. Unlike me, they were relatively sober.

I was immediately subjected to a grilling into my background: they knew little about me and I suspect they had anticipated some slick manicured trial lawyer. The head publicist finally crept away to the phone to confer with Jack McClelland, and I overheard her say, “Well, I guess he looks all right, but he’s a little West Coast.”

That was my first intimation that an author’s task was not only to write but to sell. You are not told when you sign away two years of your creative sweat that you are expected to earn your small pittance in royalties by going on a publicity tour. The publisher, of course, dreads camera-shy wallflowers or those who, in the current newspeak, are cosmetically disadvantaged.

As an aside, a major British publisher has just confessed to the long-standing practice of preferring the beautiful face to the beautiful book. Several weeks ago, I read with resigned cynicism a piece in the Guardian Weekly, and this is the lead paragraph:

“Agents and publishers in London last month confirmed what embittered old stagers have long suspected: literary success is now as much about looks as the quality of your books. Whether a new author is seen as gorgeous or not has become a key criterion in deciding whether a book gets the kind of marketing push that will give it a chance of selling. With publishers no longer giving literary authors the luxury of three or four books to find a readership, a culture of hyping photogenic young things has gripped the industry.”

The article recounted a debate at the London Book Fair at which a publishing director bluntly owned up to this long-standing practice. He went so far as to say the author of Corelli’s Mandolin would have found success earlier if he had not been short, fat, and bald.

I guess I was chosen to be the photogenic young thing of 1979, and since it is the custom of publishers to withhold all manner of secrets, they offered no advice about how to deal with the booby-traps waiting to be sprung. These tours are not only tests of stamina, but of sanity; the worst years are the early ones when you are trying to convince the public you’re not a lucky one-shot wonder.

There are not many authors who could not contribute, from their experiences, a chapter to a horror novel. I think the one I would write would be set in Winnipeg, where, several years ago, I was hyping Platinum Blues, a story about a stolen love song.

I found myself on one of those TV shows where they shuffle people from Green Room to studio, live on camera for their five minutes of local glory. The host was sweating under his toupee and seemed otherwise distracted. Clearly he was not aware that the wrong guest had been deposited on the seat beside him, and he began asking me questions about how to care for the family dog. Apparently he thought I was the veterinarian who was still waiting in the Green Room.

There are rare, sweet occasions when you are dealing with professionals, Michael Enright or Vickie Gabereau, but a more typical episode, one I think many of us can relate to, might be this: You take a forty-dollar cab ride to a radio station somewhere out in East Scarborough, because your publicist can’t take you there, she has John Updike in tow, or Martin Amis. As you introduce yourself to the receptionist you look with trepidation at the station logo, 88 FM, All Country All Day. You know immediately that whoever will be taping the interview has not read a book in the last twelve years, particularly yours.

You realize who you really are. You are not a writer. You are fill. You are Canadian content.

And you wait. Station personnel scurry about, they engage in desperate whispered conversations, and you worry that they forgot to slot you. Can you come back tomorrow, they ask. You have to explain that tomorrow you’re in Edmonton.

Someone finally races in with a tape recorder, a breathless cherry-cheeked apprentice who apologizes because she’s only read half of the first chapter. At least she’s honest. I get a kick out of those interviewers who fake it—they can’t bring themselves to admit they haven’t read the book but they’re eager to have you sign it so they can give it to their aunt for Christmas because she likes to read occasionally.

Or there’s the graduate student at the local university station who is determined to deconstruct your novel, asks questions you can’t comprehend, snidely demands to know whether popular fiction has intrinsic cultural merit, then proceeds to give away the entire plot. Your only comfort is knowing the station has an audience rating of point zero one percent.

And then there are the so-called hot-line shows … where no one phones in. You’re staring at the host’s telephone console praying that one of those lights will start blinking before the commercial ends, and when someone finally does call in, he’s complaining about the sewer rates in Burlington or wants to know your views on animal testing.

You fly into Saskatoon for an anticipated full schedule and the publicist greets you with, “It’s not a heavy day,” and of the two interviews scheduled one has to be cancelled because the host of Good Morning Saskatoon is still in detox.

So the publicist fills with visits to bookstores, and you wander into Chapters to sign a bunch of your books, and the acne-faced floor manager apologizes because they didn’t order enough and they’re all gone. You’re reminded of a remark by Calvin Trillin:. “The shelf life of the modern hardback writer is somewhere between the milk and the yoghurt.” When you finally find the town’s last surviving independent bookstore, there are lots of books but no customers, and you spend half an hour commiserating with the owner because the superstores are driving her bankrupt.

Another aspect of the writer’s life of which I was unaware in my early naiveté, is that we must read aloud to people. We usually do that in libraries. You earn a little side money doing this, and can usually cadge a free dinner. Often, if the library staff is on its toes, you get a good audience.

But there are disasters. You make your way to the Inglenook Public Library and find two people waiting for you and one is the town drunk looking for a place to stay warm and the other is your only fan, who has brought in half a dozen books to sign and you can’t look him in the eye.

Remember the first time you read from your latest book, and stumbled over a misprint that had escaped proof-reading? I found one in Trial of Passion, and my listeners wondered why I stopped in mid-sentence and said, “Shit.”

I’ve been compiling a list of the questions most commonly asked at these events.

“How do you arrange your working day?” This is from the earnest young mother who has two children in tow, the kids who shuffled and whined throughout your reading.

“How to you get a publisher? How do you get an agent?” You feel forced to explain. Normally you can’t get a publisher unless you have an agent. And you can’t get an agent unless have a publisher. They stare at you blankly, trying to absorb this conundrum.

“What is your working routine?” You don’t want to boast about your steely self-discipline because that will only depress the questioner—he harbours literary ambitions, you faintly remember him from a writers’ workshop.

You explain sternly that in this trade there is no time clock to punch, you must exert a will of iron. You recount how you leave for your writing studio promptly at ten every day, imbued with determination. But you can’t help notice the weather is fair, for a change it’s not raining, so perhaps a walk in the woods might invigorate the mind, and the field mushrooms are out and perhaps one should gather some for dinner.

I came upon a wonderful phrase by the German physicist, Helmholtz, who said great ideas come not at the worktable or when the mind is fatigued. My best ideas, he said, “come particularly readily during the slow ascent of wooded hills on a sunny day.”

Many among the unenlightened do not have a proper appreciation that doing nothing is actually part of a writer’s work. Robert Penn Warren describes as a kind of discipline taking pencil and paper and going out and sitting under a tree. Discipline resides, he said, in “the willingness to waste time, to know you have to waste a lot of time.”

Indeed, William Faulkner is said to have divorced his first wife because she could not understand that when he appeared to be staring idly out the window he was actually hard at work.

Ultimately, after a couple of hours of this kind of hard discipline, you take your bag of mushrooms to your studio and sit down to keyboard and monitor. But first you have to turn on CBC FM and listen to the news, and that’s followed by the Brahms second symphony, and it would be insulting to the master not to listen. And in the meantime, of course, there’s that unfinished chess game on the computer that might just sharpen the mind—to be followed by a few rounds of computer bridge. I have yet to fall prey to internet addiction only because I have banned all phones from my studio.

Suddenly you realize yet another hour has passed, and you sense within the first tremblings of panic disorder, and you finally bring up the chapter you’ve been working on, and you begin to read, to edit, to compose—and then just as suddenly it’s seven o’clock and you’re late for dinner and in deep shit and you race to the house forgetting your bag of mushrooms.

Art may be a jealous mistress but is nothing as compared to the wrath of a wife who is about to be late for a meeting of the Pender Island Fall Fair committee.

Here’s a question we all like: “How much money do you make?” Or you get this one: “Do you have any control over what goes into your dust jacket?” She wants to say: that picture makes you look younger than you really are, they must retouch those old photos. This is the one I fear the most: “Mr. Deverell, I wonder if you’d have a moment later to look at something.”

This is the gentleman who pulls you aside over the cookies and coffee – he has never actually read one of your books, but he has written his own 800-page saga, about his struggles with the corrupt courts, about his wife’s lying allegations of abuse—and he wants to know if you could put a word in with your publisher.

Louis Dudek once remarked that fame is the privilege of being pestered by strangers. Or you might prefer the definition by the Calgary iconoclast Bob Edwards: “Fame, from a literary point of view, consists in having people know you have written a lot of stuff they haven’t read.”

Sometimes you give readings in stores, but that’s usually done jointly with, say, the former NHL star who’s just had a ghost writer churn out his autobiography, and he has fifty people in his line for signings, and you have three. Sometimes you read in schools. Can there by anything more deflating than sitting in front of a group of shuffling teenagers who are waiting for the bell to ring?

Another question commonly asked: “Do you draw on real people for your characters?” This is an awkward one, given the laws of libel, but all fiction writers must admit to a little such plagiarism, mostly of friends, occasionally of enemies. My bêtê noir when I was in practice was a conniving prosecutor, a charter member of the old boy’s club and a foul-tongued master of locker-room humour. Ultimately of course he became a judge. He has passed on to an even higher court, so I may freely tell this story.

I sought to wreak revenge on him for his various misdeeds by portraying him in one of my early novels. This I did with fearless precision, and I was somewhat alarmed when this particular high court judge approached me one day in the Vancouver courthouse. He told me he thought my latest was my best and that all my characters rang true. It’s odd how some people cannot recognize themselves in the mirror.

Not all characters come, of course, from life, except as patchwork figures made of scraps of reality, but sometimes they take on a life of their own. Or, to be more exact, they enter the life of the writer. I have been known to become the character I create, to the dismay of those around me who must endure the tedium of listening to me recite like a Buddhist guru or a depressed eco-neurotic jungle guide – that’s this fall’s book. My latest incarnation, in my work in progress, is a neurotic psychiatrist who is himself undergoing analysis. People avoid me because I am constantly analyzing their dreams.

Here’s a twist on that theme: sometimes another person enters the life of the writer. Six weeks ago, I learned I have an impostor. This is the e-mail that arrived:

“Dear William Deverell, I was wondering if you could do me a huge favour. Send me a signed photograph of yourself. The reason I ask is complicated. When my uncle died two years ago, my Auntie went mad suddenly for dating agencies, alcohol and holidays abroad. A month ago she found a boyfriend named Ray Duval who claims to be Canadian and write under the pseudonym, William Deverell. On meeting me he handed me a copy of your paperback Mindfield and said, ‘this is one of mine.’ He also showed me a poem of very, very poor quality. I am a young Welsh author who had my first novel published at the age of 21 and I knew instantly that the works were by different people. Hence my search for the real you. When I found your website I confronted him with a printout and he now claims he and his publishing company, Mandarin Paperbacks, will sue you for copyright infringement. My aunt in her lonely foolishness believes him hook, line and sinker. For my own sanity please send me some identification, autographed.”

Since the message arrived shortly after April Fools Day, I played with the thought I was the target of a Machiavellian practical joke, but no, various researches have established that this young woman exists, as does her gullible and doubtless sweet auntie. I have sent proof that I am the real me.

Let me turn to another question commonly asked: “How did you become a writer?” Allow me a few minutes to make answer.

I never wanted to be a lawyer. All my life I have harboured only one secret shameful fantasy, and I am living it. I have found early proof of this fantasy while in the process of assembling my archives for the University of Saskatchewan, my alma mater. I came upon a mouse-nibbled scrapbook deeply buried in a trunk. It was a sporadic attempt at a diary, and it swept me back to those years of middle teens.

Carol Shields once remarked, “There are chapters in every life which are seldom read, and certainly not aloud,” but let me risk reading an early chapter of mine.

Listen to the voice of this angst-ridden yet swaggering adolescent: First entry, April twenty-fourth, 1954—“I am feeling very dispirited today, so I decided to start a diary. A funny thing about this diary is that I hope it will be read by posterity. Someday I may shock the world into noticing me. I hope to be a great writer.” Forgive him, for such splendid arrogance is the province of youth. The great writer goes on: “I’m dispirited because I’m afraid I’m falling in love with a girl. I wouldn’t mind that very much, except that the girl seems to be quite bored with me.”

Entry a few days later: “Ruth is babysitting. I tried to phone her. But I botched it. I can’t speak on the phone to girls. I had wanted to go to The Cruel Sea with her. No dice. I think she is giving me a gentle hint to stay away. Warner and Frier are going to see I the Jury. I pity their intellects. It’s about 7:30 now. I’ll go to The Cruel Sea by myself, I guess.”

Home was Regina. I grew up in the tough end of town, the north side, attended an institution called Scott Collegiate. My reflections on school: “We are going to be tested on some poetry, Browning and Shelly. How can someone be tested on something he loves? I’m goddamn sick of school. What a waste of time and energy.”

A week later: “It’s Saturday. I’ve been neglecting my diary. Nothing is happening. Finished reading To Have and Have Not. Ruth refused another date.”

On the next page the diary takes on a staccato tone: “I begin to have regrets about diary. It is ridiculous. Passed Ruth on the street today. She was with a girlfriend. She said, ‘Hi.’ I said, ‘Hi, Ruth.’ Warner is trying to convince me to be bold with her, but I can’t.”

Following that: “Went to an art gallery today. Student paintings. Some are all right. One of Ruth’s was there. I was prejudiced and thought it was good, but my unbiased opinion is that it stinks.”

Here’s our young hopeful getting into politics: “Most interesting thing of this week is our coming election at school. I plan to start a political party to run candidates for the eight posts.”

May 26, 1954: “Reaction sets in. I worked my heart and brain out for a bunch of dull dolts to get elected.”

A cry of anguish:

“It was I who conceived of forming a political party. It was I who convinced Eleanor to run. It was work to keep her going. It was I who convinced Frier to run. That was harder. It was I who brought Mitchell in with us, despite objections. It was I who got Lois Fritzler to run, perhaps our only safe candidate. It was I who got some expensive bristle board from Service Printers. I hate appeasement, so I walked out.”

Entry the next day: “Eleanor lost the election by one vote. They’re having a recount. Delva, Mitchell and possibly Emily would have won if I had been allowed to manage their campaigns. I voted for Frier and that’s all.”

Here’s my final entry: July 24: “I had stored my diary away. Just a while ago I opened it to glean over old memories. It makes me sound like a psychopathic freak. My mind sounds unbalanced. I’d like to go out with a girl tonight.”

I made another stab at a diary a year or so later: “Now I am seventeen years, two months old, and I believe I should recap my literary career.”

It was, I’m afraid, a pitiful career, consisting solely of having won, in public school, a citywide essay contest with an auspicious reward – the promise of publication. A children’s magazine, Owl or Chickadee, one of those, would publish anything I would care to write.

This was the beginning of a case of writer’s block that could almost be classed as pathological. I couldn’t do it. I was overwhelmed by a fear of failure that continued to haunt me through my teens and early adulthood. Occasionally, during my years as a journalist, I tried my hand at fiction, but my trials were imperfect, incomplete, and what I produced I had not the courage to send anywhere.

This fear of failure drove me to the law. I shelved my dream of writing, stuffed it in a closet where I wouldn’t have to face its steely glare. That dream collected dust for decades. Though I suppressed it, I was tortured by it, haunted by the whisperings of a forsaken muse.

But an internal pressure was building, fuelled by a fear I might live out the rest of my life plagued by the guilt of never having tried. I was at that fearsome age of 39, so this was the classic archetypal mid-life crisis. When I announced to my partners I was taking a sabbatical from practice to write a novel, I could hear them muttering: “His mind is gone.”

I don’t think I have ever fully thanked Tekla for encouraging me to do this, to run off to the solitude of the Gulf Islands while she strove in the city as a counselling psychologist, homemaker, and mother of two teenagers, and it was with great trepidation that I walked out of the closet, dusted off the dream, and took it to Pender Island along with an old upright Remington, a box of blank paper, a three-volume Webster’s dictionary, a first edition of Fowler’s Modern English Usage, and that slim masterpiece by Strunk and White called The Elements of Style.

You all remember E.B. White’s jaunty forward, his reminiscence about his mentor, Professor Strunk:

“‘Omit needless words!’ cries the author ... and into that imperative Will Strunk put his heart and soul. In the days when I was sitting in his class he omitted so many needless words… that he seemed in a position of having short-changed himself, a man left with nothing more to say yet with time to fill… [He] got out of this predicament by a simple trick: he uttered every sentence three times. ‘Omit needless words! Omit needless words! Omit needless words!’”

My difficulty was that I had no words to omit. Nor would plot or character come. My intention had been to write a serious novel – god forbid I would lower myself to popular fiction – but all I managed to squeeze out were a few dribbles of descriptive prose. I stared at that Remington, memorized every bolt and spindle, began talking to it. I hiked, I biked, I scuba dived, I hung around with the locals at the bar. Weeks passed, months dragged by. Had I lost the use of the right side of my brain? Had too many years of exercising the left side, unravelling the quirky logic of the law, caused it to atrophy?

But I was to learn that the root of my problem lay elsewhere: I had been brought up by a literary father, brilliant and self-taught. A journalist, a voracious reader of classics who had learned German so he might read Goethe and Schiller without the impediment of translation. He quoted Shakespeare on occasions appropriate or not, recited Keats and Shelley when in his cups—which regrettably was not an uncommon condition – and regularly insisted I would be better off reading Moby Dick than the Lone Ranger.

My mother, for her part, devoured mystery novels, and she would simply, with her usual grace, shrug off Bob’s withering denunciations of formulaic fiction.

Secretly, he wrote—stories that he mailed off to the New Yorker but that never saw the light of print. He showed me such a piece once, and with all the cool superiority of the teenage snob I was, I praised it insufficiently, and I don’t think he wrote after that, and I have ever since carried the burden of my impertinence.

Even his last words to me, by long distance from Saskatoon, as he lay dying of cancer, were borrowed from a literary master: “The reports of my death are greatly exaggerated.” But they soon turned out not to be, and I flew to Saskatoon too late. He had known I was writing a novel. He had had a dream: me, his son, buried in piles of paper.

If that was his dream, I was determined to make it mine.

As of that time, I was still suffering under the grinding weight of my writer’s block, despite several blind forays into a self-conscious Can-Lit style that I assumed was demanded by the industry. But suddenly I underwent a catharsis. It was this: I had been afraid to write because of my father, afraid to follow in the footsteps of his failures, but also cowed by something larger, the sense that I would disappoint him if I did not follow the true and noble path—produce a work that would attract that adjective he most admired: “literary.”

Despite my sadness at his death, now I was unchained, I was free to junk earlier efforts. I had been a criminal lawyer, I had defended the innocent and the guilty and prosecuted the vilest murderers. I knew something of the underbelly of my city, Vancouver, I knew something of the pompous theatre of the courtroom. I was nearing forty, I was determined to break into print with both guns blazing. I would write a thriller.

I found justification from G.K. Chesterton: “Literature is a luxury, fiction is a necessity.” But Hilaire Beloc may have better described my purpose:

“When I am dead, I hope it may be said:

His sins were scarlet, but his books were read.”

Suddenly it was as if a dam had been breached, and I was drowning in a torrent of my own words. I was startled and awed, and I found myself muttering to my typewriter, “My God, Remington, I think I can write.” I suddenly had a concept, a story, I had twisted characters and twisted plot. Needles would have a psychopathic killer seeking vengeance against a prosecutor.

As an anecdote, the germ of this plot was to be found in a murder trial I prosecuted, a thrill killing with macabre literary nuances. The accused had found himself absorbed in a thriller by Lawrence Sanders called The First Deadly Sin, in which a psychotic murderer seeks orgiastic pleasure through his deeds. As a sick form of plagiarism, the defendant had copied the crime. As he was being led away after being sentenced to a life of imprisonment, he slowed by my table and said in a low voice: “Some day I’m going to get you.”

I later learned he escaped. So upon occasions like this I always tend to look about to ensure he is not lurking among the audience.

Though I had some sense of foreordination that Needles would be published, I wasn’t cocksure, and I will tell a guilty secret as to how I ensured my manuscript would not perish at the bottom of a sea of entries for the Seal Prize. One of my partners at the time—she is now Madam Justice Nancy Morrison—was a close friend of the late Judy Lamarsh, whose political memoirs had just been published by McClelland and Stewart. I forever honour Ms. Lamarsh’s memory for personally handing the manuscript—we’re talking about 600 pages here, by the way—to Jack McClelland.

It was later reduced to half of that, a painful surgical process in the manner of limbs being amputated.

Jack McClelland is one of my heroes, a great showman, and not above employing the most disreputable devices to ensure a book might achieve the notoriety that boosts sales. Everyone hates lawyers, he warned me, especially critics, and they will utterly despise a lawyer who won fifty thousand dollars for his first book. So he devised an idea that was bound to inflame this animosity.

I became aware of it only when I looked one morning at the front page of the Vancouver Sun. The zipper – the human-interest item at the bottom of the page – began thus:

“Bill Deverell’s Toronto publisher is needling book reviewers across the country to make sure they get the point about the Vancouver lawyer-author’s new novel, Needles. The book is a courtroom drama set against the background of the Vancouver heroin trade so in an effort to promote it McClelland and Stewart mailed hypodermic syringes to the media. Complete with attached hollow needles, several hundred of the disposable syringes have been mailed to book editors across the country.

“‘You’re kidding,’ was Deverell’s reaction when the Sun told him about the promotion. ‘Anything in them?’ he asked.

“But the one-time Sun reporter knows a good headline when he sees one.

“‘The needle is part of the hype,’ he said.”

My first inkling that Jack’s publicity coup was to cause undesirable fallout came with the book’s first review, also in the Sun. It began by quoting a section of the Criminal Code of Canada:

“Any publication the dominant characteristic of which is the undue exploitation of sex or of sex … and crime, horror, cruelty and violence shall be deemed to be obscene.”

The reviewer proceeded as follows:

“The author of this unwholesome collage of sex, crime, horror, and violence is a Vancouver lawyer with considerable experience in criminal law. He should know that a decade ago, before decency was outmoded, his book would have risked prosecution under Canada’s obscenity laws. Today, in our permissive society, the book wins a literary prize. It is a thoroughly nasty book...

“None of his characters, including police officers and lawyers has any redeeming quality. The single exception is a judge. Lawyer Deverell prudently avoids sticking it to the judiciary.”

I have since made up for that oversight.

I take comfort from Malcolm Lowry. In a letter following publication of Under the Volcano, he wrote, “The sales in Canada have been two copies, and my sole recognition here is an unfavourable squib in the Vancouver Sun.”

My second novel, High Crimes, was about an audacious gang of Newfoundland drug smugglers, and was frankly fact-based. My reputation was not much enhanced by a Canadian Press review which was reprinted in dozens of newspapers. The lead paragraph read simply, “William Deverell is back on drugs.” That made for easy work for the writers of the headings, and invariably they read as follows:

“William Deverell is back on drugs.” “Deverell Back on Drugs.” “Award-winner Deverell is back on drugs.” Ken McGoogan interviewed me for the Calgary Herald, but couldn’t escape the temptation, though he offered a twist: “Lawyer still on drugs, vows to quit.”

My more recent books may show no evidence that I have beaten the habit, but they do suggest I have been trying to escape from the chains of the criminal genre – I’m still haunted by childhood literary abuse, but it is no easy task to escape a life of crime. Or to write – if I may dare call it – bloodless prose. When I finally produced a book without a murder, it won two crime fiction prizes. I haven’t killed anyone since, but the genre won’t let me free from its clutches.

To the extent that my current creation, the neurotic psychiatrist, has subsumed me, I have found myself voraciously poring through psychiatric texts, seeking, as he does, to understand the artistic impulse. As the novel begins, my protagonist has just been abandoned by his long-term partner, a visual artist, and he is struggling to grasp the artistic impulses that drive her.

So I thought that for the remainder of my time here, I would share some of my research into the artistic urge, that itch to create from which we all suffer.

First the good news: A comprehensive study of artistic creators at Berkeley inspired the authors of a popular psychology text to list these traits that were found to characterize creators.

Independence of thought, not interested in activities that demand conformity, not easily influenced by social pressure.

Tendency to be less dogmatic in their view of life than those rated as not creative.

Willingness to recognize their own irrational impulses.

Preference for complexity and novelty. (One researcher hypothesized that this reflects a desire to create order where none appears.)

A good sense of humour.

High emphasis on aesthetic values.

The conclusion drawn by these investigators seems both natural and agreeable: because creative persons are more flexible they face fewer obstacles to problem-solving. In their next breath, however, the authors of this text go on to pop the balloons of conceit:

“The reader may now be wondering why we have not listed intelligence as the prime characteristic of creative individuals …

“Beyond a certain level there is little correlation between scores on standard intelligence tests and creativity. Some of the most intelligent persons are rated lowest on creativity. Among artists such as sculptors and painters the correlation between quality of work and intelligence is zero, or slightly negative.”

I have checked out this study, and I am able to assure you that writers scored somewhat better.

I would add a further quality which has been amply demonstrated to me during my 21 years of pleasant association with members of this Union. Not only are most writers less dogmatic and conformist, they tend to a high social conscience and many, I am happy to say, can be counted on to be in the front ranks of opposition to a society which marginalizes its artists, who oppose the new world order in which culture, health and environment are held hostage to the market place, who share an ideal with those who stood outside the barricades of Seattle and Quebec.

One cannot write without a conscience.

But are we also diseased? There exists a school of thought that writers suffer a compulsive disorder that forces us to the page. Juvenal, in the Satires, put it bluntly two millennia ago: “Many suffer from the incurable disease of writing, and it becomes chronic in their sick minds.” That brief thesis has survived the centuries, and we still speak, in the words of Henry James, of “the madness of art.”

That great explorer of the undiscovered self, Carl Jung, was once called upon to address a convocation of German poets, and he chose as his theme “the divine frenzy of the artist,” which he says “comes perilously close to a pathological state…” He reassures us, you will be relieved to know, that “only when its manifestations are frequent and disturbing is it a symptom of illness.”

Jung speaks of art forcing itself upon the author: “… his hand is seized, his pen writes things that his mind contemplates with amazement... While his unconscious mind stands amazed and empty before this phenomenon, he is overwhelmed by a flood of thoughts and images which he never intended to create and which his own will could not have brought into being …” In a poetic phrase, he calls these images “bridges thrown out towards an unseen shore.”

He advises us to think of the creative process as an alien impulse, “a living thing implanted in the human psyche which can harness the ego to its purpose.”

So there you have it. We are led by an alien impulse. Like characters from speculative fiction, we are walking about with living implants in our psyches. To be fair, he was writing primarily of poets here.

The biographies of great artists, Jung said, “make it abundantly clear that the creative urge is often so imperious that it battens on their humanity and yokes everything to the service of the work, even at the cost of health and ordinary human happiness.”

Sigmund Freud offers an even more dour analysis: he would regard us not only as slightly ill but dreadfully unhappy. This is from a piece called “Creative Writers and Daydreaming:”

“The creative writer does the same as a child at play. He creates a world of fantasy which he takes very seriously, that is, which he invests with large amounts of emotion – while separating it sharply from reality.” And he goes on to say, with utter confidence: “We may lay it down that a happy person never fantasizes, only an unsatisfied one. The motive forces of fantasies are unsatisfied wishes and every fantasy is the fulfilment of a wish.”

But he is not finished shattering any smug self-images we may hold: we daydreamers are overcome with shame and guilt. “The daydreamer carefully conceals his fantasies from other people because he feels he has reasons for being ashamed of them. Such fantasies, when we learn them, repel us or at least leave us cold.”

Still, Freud finds hope for the creative writer, whose personal daydreams, he says, can induce great pleasure. “How the writer accomplishes this is his innermost secret, the essential ars poetica lies in the technique of overcoming the feelings of repulsion in us.”

How, you may ask, do we overcome this repulsion? “We can guess two of the methods – the writer softens the character of his egoistic daydreams by altering and disguising it, and he bribes us by the aesthetic yield of pleasure he offers in the presentation of his fantasies...”

Freud makes the process sound utterly conniving, and I wouldn’t doubt he was in one of his sour moods when he composed this. Maybe he had just got a bad review.

But Freud refrains from portraying us entirely as beyond salvation. We writers have a useful therapeutic role to play: “The enjoyment of an imaginary work proceeds from a liberation of tension in our minds. It may be that not a little of this effect is due to the writer’s enabling us to … enjoy our own daydreams without reproach or shame.”

Dr. Otto Rank was an early follower of Freud but he ultimately took a divergent and possibly risky path. He devised the concept that male creators are motivated by jealousy of female procreation.

The great psychiatrists don’t offer a cure for what ails us. Sigmund Freud: “The nature of artistic achievement is inaccesible to us. Science can do nothing toward elucidation of the artistic gift.” When asked to publish his theories on sexuality, he himself replied as an artist might: “If the theory of sexuality comes, I will listen to it.”

Karl Jung: “What then can analytic psychology contribute to the mystery of artistic creation? … Since nobody can penetrate to the heart of nature, you will not expect psychology to do the impossible and offer a valid explanation for the secret of creativity.”

Though he tenders a theory that art comes as eruptions from the collective unconscious, he joins Freud in abandoning us to a mystery that must fascinate us all.

And while studies have shown that creative artists rank in the upper fifteen per cent of the population in psychopathology – we score high particularly in the hysterical and paranoic disorders – we also rank in the upper levels of ego strength. As one observer put it, we are both sicker and healthier than those with less artistic bent.

But let me not leave the topic without quoting some sunnier observations from proponents of self-actualization: “The mainspring of creativity,” says Carl Roger, “is curative. Man’s tendency to actualize himself, to become his potentiality, is evident in all organic and human life. Creativity … is a quality of protoplasm, there is creativity in everyone.” Maslow speaks of the “peak experiences” particularly enjoyed by artists. Rollo May tells us we are characterized by an intensity of awareness, a heightened consciousness.

On that more reassuring tone, I should conclude, because I note the bar is about to open, and I sense, particularly among my fellow writers a stirring and a thirst. In thanking the Writer’s Union and the Writer’s Trust of Canada I can think of no better exit line than this quote from a magazine piece written 40 years ago by Hugh Garner. “A short time ago Morley Callaghan and I were talking typical writers’ talk—about our current work, critics, publishers… Before we parted Callaghan said, ‘Being a Canadian writer is tough, isn’t it?’ I answered, ‘Well, it sure beats working in a pickle factory.’”